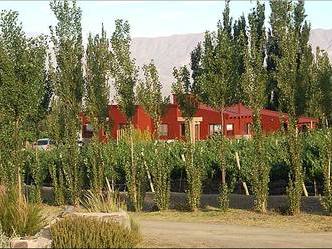

We had arrived through the dust of Route 40, from Colomé into Cachi, in an evening that promised stars. Fortunately, Erick, from the Sol del Valle inn, best known as the A.C.A. inn, gave us a warm welcome.

After recovering from the trip, we accepted the chef’s recommendation and tasted delicious rabbit au vin rouge which we finished off with a port sabayon, final touch to happily call it a day. Cachi waited for us the following morning.

Located on the west of the Province of Salta, lying at the foot of the Nevado de Cachi, 6,720 meters high, its valley locks the richness of the indigenous past.

Cachi City Tour, White Town of Mine

At about 9 in the morning, we had breakfast in the open gallery overlooking the lawn, a great balcony to Cachi’s hamlet. The way the quiet northern villages are, their history and cultural roots are discovered while wandering about their small streets, their adobe houses, their narrow ever sunny sidewalks.

Under this premise, we left the comfortable nook of the inn to hit the road again and go around Cachi.

Enigmatic Cachi

Its name is a mystery. It might be attributed to the quechua word for “salt” or to the diaguitas’ kakana tongue in which kak means “crag” and chi means “silence, solitude”. It was these natives who first settled around the Nevado (snow-capped mountain), developed their economy based on crops and projected ingenious irrigation systems later imitated by the Spaniards.

After the Conquest, the Jesuits had founded several missions in the valley and when the lands for encomiendas were distributed in the year 1673, those corresponding to Cachi ended up in the hands of doña Margarita de Chávez. After 1719, the owner of the land, Felipe de Aramburu, gave origin to the Hacienda de Cachi, the estate that locked the town for years, organizing all its growth.

We walked along Bustamante Street to retrace our steps along what is known today as the old town which keeps the buildings from colonial times, its cobble and rubble streets with irrigations canals on the sides.

The area called “new town” also used to be part of the estate, which around the year 1946 was expropriated and divided into lots. In those 10 hectares of land adjacent to the old settlement, the hospital, the school and the police station were built.

The main square 9 de Julio dates back from the XIX century and is surrounded by cobble paths and houses with stone bases, their walls whitened with lime and sand, with cardon cane ceilings, covered with mud and wrought iron bars.

To one side lies the Saint Joseph church, which in addition to religious activities, used to perform the task of consolidation of the use of the Hispanic tongue in the estate producers. Declared national historical monument in 1945, made of pebbles with wide adobe walls and a bulrush in the front crowned with three bells typical of the XVIII century. In the inner side, the 35-meter-long aisle with two transversal chapels ends up in arches painted in white over which cardon boards rest. There the image of the town patron saint, Saint Joseph is sheltered among other saints.

To the right of the temple, the Archeological Museum occupies an ancient house dating from 1920, with a Neo-Gothic gallery that forms a roofed terrace. Organized by a group of archeologists during the 1970s, the museum has more than 5000 pieces that witness the social organizations previous to colonization, backed by countless scientific excavations done in the area.

Reconsidering our history, we went back to the high cobble and sandstone sidewalks. To the quiet morning of a town that struggles between the silent past and a present that is getting more and more crowded with travelers and visitors.

Karina Jozami

Eduardo Epifanio

From Cafayate, passing by Colomé, 134 km are traveled along National Route 40.