The Subfluvial Tunnel offers a fascinating journey that starts by the bounteous Paraná River and continues under its waters until the opposite bank is reached in the neighboring Province of Santa Fe.

"Man usually does amazing things and, in his eagerness to create, he sometimes matches nature; sometimes he succeeds and sometimes he does not. The tunnel, I think, is a success", one of the guides asserted during the tour.

Immersion

Going down Gobernador Uranga Avenue up to the Nautical Club, the toll barrier and the vehicle height control are the last bastion of solid ground before the road starts to leave the shore of the City of Paraná behind and gets deep into the mysterious territory of the river and its depths.

Once near the entrance of the tunnel, the motorway goes down gradually. The river lies very close and the sun beams get mingled with the bright electrical lights. This is a transition area to get the eyes used to the new lighting. In a matter of seconds, the underwater journey begins.

A Monumental Masterpiece

The Uranga - Silvestre Begnis Subfluvial Tunnel, formerly called “Hernandarias Subfluvial Tunnel”, is almost 3 kilometers long and joins the City of Paraná in Entre Ríos with Santa Cándida Island, in the neighboring Province of Santa Fe, thus connecting the road networks in both provinces.

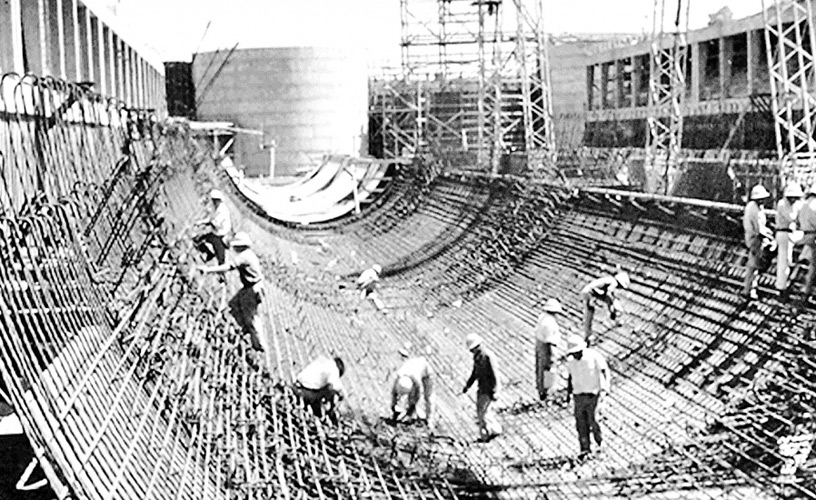

It is made up of 37 cylindrical tubes of reinforced concrete measuring 65 meters of length, 10 meters of diameter and 4,500 tons of weight each, with 50-centimeter-thick walls. The assembled segments rest on the river bed which lies 30 meters under the water.

As safety is one of the most important aspects of this enterprise, the impeccable concrete walls show traffic lights, sign posts, emergency telephones and services every hundred meters.

The tunnel has a closed circuit TV system, loudspeakers to give directions to the drivers, fire alarms and detection devices to control leaks and the level of carbon monoxide in the air.

In addition to the lanes along which vehicles travel and the emergency pedestrian path, the tunnel contains two smaller passageways (one above and another one below the road) built for maintenance works, gas extraction and circulation of air, pumped by two enormous ventilation towers rising on both ends of the complex.

Two Provinces Embrace

The need to overcome the geographic isolation imposed by the river used to be covered by rafts that would carry vehicles from one shore to the other. For over 40 years, the rafts, the pontoons and the ferry boats were part of the daily life and culture of the region.

When this system became obsolete due to the increase in the number of vehicles that needed to cross the river, Governors Raúl Uranga and Carlos Silvestre Begnis gave origin, in 1960, to a treaty between the two provinces, which triggered out the construction of the majestic masterpiece that was named after them.

The project was completed by three companies (one of them German, another one Italian and an Argentinian enterprise) and it cost almost 60 million dollars. The works lasted seven years and engaged up to 2,000 workers including operators, engineers and specialized staff (due to the depth and bad conditions of the river, the help of 15 SCUBA divers as well as fishermen and locals who knew the area very well was used everyday).

The Other Shore

As the end of the tunnel is reached, the slope becomes steeper and daylight returns gradually once the surface is hit.

Ahead: the City of Santa Fe and its live history welcome travelers with open arms. Behind: cozy Paraná and the deep and plentiful river wait for visitors to return.

The guide was right: in this case, man seems to have done things right. Only nature and time will have the last word.

Pablo Etchevers

Gentileza Tunelsubfluvial.gov.ar